An older grey-haired Lao woman in a lavender cardigan and a black-and-floral wrap sits on a cement bench outside her family’s shop. She sits next to dozens of dark green squares of cut river weed, spread over the bench and a bamboo basket. They’re covered with sesame seeds and drying in the sun. Most of the shop’s customers are Lao. They stop by to pick up snacks, chips, sunflower seeds, beer, lighters and cigarettes.

The shop and the bench are on a quiet street in the ancient capital of Luang Prabang, next to a popular papaya salad stand and across from a temple: Wat Nong Sikhounmuang. Built almost 300 years ago, it allegedly holds the largest Buddha statue in Luang Prabang. Its three-tiered golden roof is adorned with 14 nagas, magical serpents of the Mekong River.

The Lao woman tells me the river weeds are khaipen: an algae harvested from the Mekong River, its banks just a block away, or from its tributaries around Luang Prabang. Her mother learned to make it after moving out of the mountains and into Luang Prabang and taught her when she was young.

She says the khaipen is harvested in the cool season after the monsoons have ended, when the rivers are flowing clean and the water levels are lower. Local families, farmers and fisherfolk cut the khaipen from the riverbed, pounding, cutting and washing the weed in a flavoured broth before spreading it to dry and sprinkling it with seeds. Sometimes they add fried garlic or onion but this woman doesn’t.

Khaipen sheets are roasted or flash-fried and eaten on their own as a snack or with chili dips. They’re sold by the bag in markets and a standard on Lao menus. They’re stiffer than Japanese nori, the seaweed used for sushi. Khaipen are Lao potato chips, Lays from the bottom of a river. They’re even slightly ruffled.

Food in Laos has a lot in common with the cuisine of neighboring Thailand: intense flavors, family-style shared dishes and ingredients—chilies, garlic, lemongrass, galangal, ginger, fish, oyster and soy sauces, rice, noodles. The languages of the two countries are very similar and Laos maintains strong ties to Thailand’s northeastern Isaan region.

But eating Lao food means branching out a little from the standard fair of Thai kitchens, beyond coconut-laden curries and stir fried noodles to chili pastes, fermented fish, and some more dense and less accessible or familiar flavors.

Eating Lao also means embracing sticky rice. While common in Thailand, sticky rice is nearly ubiquitous in Laos. Khao niao, as it’s known, is steamed for hours in a bamboo basket called a huaht and eaten with your fingers, dipping it in curries or using the rice to form a kind of scoop.

The food in Laos is diverse: traditional meals vary dramatically among ethinc groups, from lowland Lao Lum to upland Lao Theung, Hmong, Yao and Khmu communities. The differences reflect groups’ culture and history: gathered and foraged foods, like khaipen or wild cassava and yams, have historically been vital for groups living outside the lowland cultivated agricultural hubs.

The cuisine is also sown with influences from French colonial rule—baguettes and paté—and migration from Vietnam and Thailand, and more recently from China. Sandwiches and baked sweets are common. Many towns also have a restaurant or two serving Indian food.

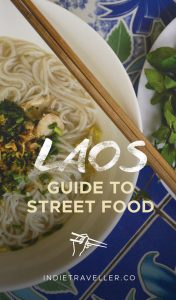

What follows are some of the best and more unique dishes Lao food has to offer. It’s a short guide to enjoying Lao street food and appreciating the differences between Lao food and Thai food.

The details of dishes will change from town to town and from the city to the countryside. Different areas of the country have been impacted in distinct ways by migration, colonial rule and the reach of the Lao kingdoms: Lan Xang, Luang Phrabang, Vientiane and Champasak. This comes out in the country’s food—Vietnamese influences, for example, are generally much stronger in central and southern Laos due to migration during French colonial rule.

A general rule of thumb: if it smells unfamiliar but the Lao guy next to you seems to like it, eat it. You’ll be happy you did. At least in retrospect.

Sin Dad

Sin dad is a classic social meal in Laos, a mix between hot pot and barbecue at your table. It’s a do-it-yourself night out in Laos, a communal meal of meat and vegetables served with limes, garlic, chilies and hot and salty sauces.

A cruicble of coals normally sits in the middle of the table, with a domed circular pan sitting on top. The pan has holes to let the heat up and let the drippings drain. A small trough runs around the edge to hold broth. A server brings the table a platter of meat (mostly pork) herbs and vegetables and the rest is up to the group. Sin dad is a lot easier if you’re good with chopsticks but if all else fails, ask for a fork.

Jeow Bong

Jeow bong chili dip is the king of sauces and bar food in Laos. It’s blood red, made with dried chili peppers, garlic, fish sauce or padaek (see below) and a mix of other spices. It usually has shredded pork or buffalo in it but doesn’t contain any raw meat; the dish is generally heavily salted and made to be kept for a while. One of the keys to jeow bong is that many of the ingredients are fried and just a little caramelized before being pounded to a paste in a mortar and pestle. With a little raw sugar, the result is a balance of sweet and chili heat. It’s typically eaten with sticky rice, boiled vegetables or khaipen.

Jeow is also the general term for dipping pastes and sauces in Lao. If the bong variety doesn’t sit right or the chilies are too much, look for others: jeow pla hang, made with salted fish, or jeow maklen, with tomatoes. Fair warning though: most jeow have at least some peppers in them.

Laap

Laap or larb, as it’s often spelled, is serious business. I’ve known plenty of grown men who will decide in the wee hours of the morning, after a couple glasses of rice whiskey, that it’s suddenly time to make laap. Out come the meat cleavers, the chopping blocks, a hunk of meat and another bottle of whiskey.

Laap is classic in both Thailand and Laos. But while in Thailand it’s often eaten at laap-specific restaurants, laap is much more common in Laos and it just might be the national dish. In general, laap takes finely chopped and marinated pork, fish or water buffalo and mixes it with strong herbs, fish sauce and chilies. The particular mix of herbs makes laap what it is: mint, cilantro and a handful of other leaves that I don’t know the names for, but which are uniquely and inarguably laap. Laap Lao is defined by pounded and toasted rice, which gives the dish a slight crunch and a nutty flavor. It’s also called laap Isaan, for the region of Thailand just across the border. The kind eaten in northern Thailand however, especially in Phrae province, has neither of these and often takes some richer spices, including cloves or cumin.

A plate of laap is made to be eaten family style and there are enough variations that, with a little sticky rice and some fresh vegetables on the side, people will eat a meal of just laap. The most common kind is laap mu suk, made with cooked pork, but laap dip, which denotes raw laap, is a real treat if you’re willing to accept the slight risk to your digestive tract. It’s best to stick to reputable, exceptionally clean places for your laap dip. There’s also a chance that eating raw fish laab will give you Southeast Asian liver flukes, which I hear aren’t good news. Opt for laap dip kwai with water buffalo instead. Thai and Lao folks also tend to agree that another glass of rice whiskey is a good move if you’re worried about how that laap will go down.

Khao Piak Sen

While versions of Vietnamese phở noodle soup are common in Laos, a comforting bowl of khao piak sen is a superior treat. Fat, handmade rice noodles thicken the rich meat broth covering pieces of pork or hard boiled eggs. Toppings typically include watercress and mint as well as deep fried garlic or shallots and optional chili oil.

Khao piak sen is a standard dish at Lao social gatherings and parties. Though the broth and noodles take a lot of prep, the result is worth it. It’s best to find a stand that touts their khao piak rather than ordering at any old place; chances are high that they’ll also serve khao piak khao, made with rice porridge instead of noodles. Both versions are typically breakfast foods. Get to the shop before the pot’s empty.

Or Lam

This stewed curry is a classic of the Luang Prabang area. It’s also one of the best ways to try spicy pepperwood or mai sakahn, a meaty pepper vine native to northern Laos, as well as water buffalo skin. Over the past few years, Szechuan peppercorns have gotten a lot of hype for their tongue-numbing properties. But a chunk of mai sakahn puts the star of mapo doufu to shame.

Or lam consists of lemongrass, garlic, onions, chilies and meat, traditionally buffalo but now sometimes pork or beef, boiled with pounded sticky rice, eggplants and dark brown “pig’s ear” mushrooms. Some sources say the stew also takes whole citronella leaves and stems.

It’s best to order a bowl of or lam as one of a number of dishes for a shared meal, with sticky rice and a few things to temper the strength of the pepperwood.

Padaek

Padaek isn’t a dish unto itself, but any writing on Lao food would be remiss not to mention this fermented fish sauce. Much thicker than the standard fish sauces found across Southeast Asia, padaek has a gravy-like consistency and pieces of fish in it.

While other fish sauces are usually made with saltwater fish, padaek, or bla-rah in Thai, is made from freshwater fish caught in the Mekong River basin, cured and fermented in its own flavors. Lao cooks put it on papaya salad and plenty of other foods. It’s strong stuff. You’ll probably know if you eat it.

Dtam Makhoong (Papaya Salad)

Tam makhoong papaya salad is bright, fresh and soaked in umami. Made with garlic, tomatoes, chilies, sugar and lime or tamarind juice, this is another Thai-Lao shared dish, but the Lao version features fragrant padaek instead of normal fish sauce. This isn’t comparable to any fruit salad outside of Southeast Asia: it’s green, unripe papaya doused in enough flavor that it’s sometimes hard to eat without diluting it slightly with the requisite sticky rice.

Tam is the general term for any salad pounded with a mortar and pestle, characterized by the combination of spicy, sour, sweet and salty flavors. Other versions feature cucumber, various seafoods and green mango or other fruits. Eat a plate every day or two. It’s like taking your vitamins in Laos.

Khao Soi

If you’ve been to northern Thailand, khao soi is old news. But again the Lao version is a whole other creation, in some ways closer to the dish found in Myanmar’s Shan State, across the border from Chiang Mai. Lao khao soi focuses on the roasted flavor of the ingredients and is usually made with slow-cooked pork, tomatoes and no coconut milk. It’s often eaten with thick rice noodles.

Some links may be affiliate links, meaning I may earn commission from products or services I recommend. For more, see site policies.

0 comments

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Comments are manually moderated.