The Ijen volcano in Indonesia is famed for spewing blue molten sulfur and has the largest such flames in the world. The blue flames are visible only at night and were known previously only to local sulfur miners who work the night shifts there. When it got featured in National Geographic a couple of years ago, the word gradually got out about this unusual place.

I had been looking forward to climbing this volcano and seeing the blue flames, but as luck would have it I got struck by the good old traveller’s curse. A German potato meal seems to have been the culprit: I woke up in the middle of the night, ran desperately to the toilet, and threw up everything (and worse). I was sick like a dog, and when morning came I felt like I could barely walk.

I wanted to see ash and sulfur spew from a volcano, and was less keen on seeing… other… things… spewing… from… my body (okay, TMI). Luckily I was able to delay my hike to Ijen for a day so that I could rest and recover.

While my hotel was decidedly a dump, at least the surroundings were very nice. The hotel was in a cute mountain village near the volcano, which had a small coffee factory and little rows of worker houses with vegetable gardens in front. Although my room was very musty and the food at the hotel restaurant very bad, I tried best as I could to nurse myself back into shape. A visit to some nearby thermal springs later in the day helped in reviving myself and finding new reasons to live. Finally, my stomach stopped moaning and with a 24-hour delay, I was now ready to go to Ijen volcano.

Our jeep left at 1 a.m. After we got dropped off at the national park our guide wasted no time in hitting the trail. He was actually rushing up the mountain so fast that I quickly lost track of him, so myself and two other travellers had to fend for ourselves from this point on. I was glad that I had waited a day to make this ascent; if I had been even just slightly sick I would clearly not have made it, as it was a stiff climb.

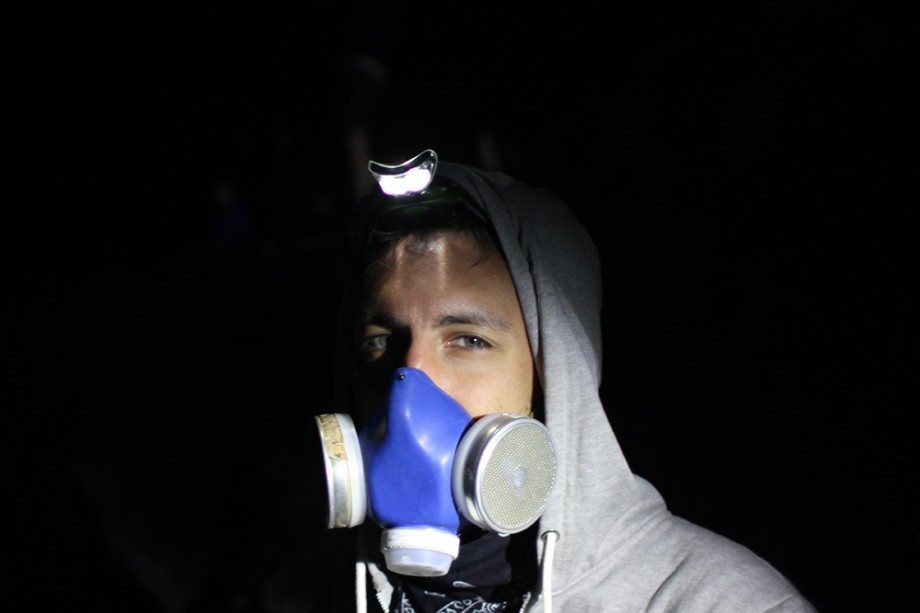

Either I’ve just started cooking meth, or I’m about to head into a volcano crater…

The night sky was full of stars and I could faintly see the Milky Way. The closer we got to the top, the more I could smell the sulfur in the air. I tried to breathe through my bandana, though this seemed to have little effect. Once at the crater itself, we were issued gas masks which made breathing a little easier.

It was another 20 minutes of descent down into the crater. I could already see the blue flames below, as well as the fumes blowing upward alongside it. The flashlights and headlamps shining in different directions along the path made it look like we were astronauts on an expedition on another planet.

When I was almost all the way down I tried to take some photos, though even with a fast lens it was difficult getting a lock on anything with barely any light around. I wanted to get close to the flames for a better angle, so I climbed down the rocks and got right next to the plumes of smoke to see the flames shooting out of the ground. But the wind changed and I got caught right in the middle of a cloud of noxious sulfur fumes that was too dense even for the mask to filter. I was breathing in the fumes while my eyes stung so much that I couldn’t see.

I imagined this must be what it feels like to be a protestor getting teargassed. Right, fuck this. I covered my eyes while backtracking up the rocks. I found myself a slightly less intense viewing spot that was a bit higher up.

I had gotten pretty hungry by now, so it was time to sit down and crack open one of the hard boiled eggs I had been given for lunch. I’m not sure if that counts as having a picnic inside a volcano. I guess not. But it was a nice egg.

From time to time, one of the miners would pass carrying baskets of sulfur back up the mountain. While the Ijen crater is an amazing attraction, you do have to spare a thought for the local miners who work here tirelessly all night, extracting big blocks of elemental sulfur and carrying up to 90 kg of the stuff up and down the mountain. The sulfur earns them a mere pittance and the health hazards clearly make this an unenviable job. A few of the miners have branched out into sculpting sulfur into small souvenirs, but for most of them just mining the material is their only source of income.

After a bit of a rest, I hiked back up to the crater rim to get there for the 5 a.m. sunrise. The reveal was spectacular; I could now see the yellow sulfur rocks below next to a beautiful azure crater lake that we had been completely oblivious to at night. As I learned later, this lake consists of pure sulphuric acid, which makes it less than recommended for a swim.

With the sun now shining its first rays I noticed a sign that had been put up at the crater rim: it’s officially prohibited to go down the crater. Oops.

Ijen is quite an adventure. I found it more exciting than seeing the nearby Mount Bromo, which is the main tourist attraction in East Java. But as with many sights in developing countries, it does feel a little strange to there for fun while other people toil away there day after day just trying to scrape together a living.

My visit to Ijen definitely stayed with me for some time. I mean this both figuratively and literally, as my clothes continued to smell of sulphur even after laundry, but it was a small price to pay for visiting such an extraordinary place.

Practical details

WHERE: Kawah Ijen volcano, East Java, Indonesia

HOW: I tried to research how to do this independently but it seemed quite complicated. A guided tour is an easier option: most tours are offered in combination with a visit to Mount Bromo, and I booked mine in Yogjakarta. I paid about 700,000 rupiah for a 3-day tour, though park entrance fees and various other extras almost doubled this amount; when comparing prices check if a tour has everything included or if you have to pay surcharges later.

PRO TIP: Avoid weekends or national holidays. I spoke to some of the guides who told me that two days earlier, on a national holiday, the number of domestic tourists coming to Ijen had been huge.

Some links may be affiliate links, meaning I may earn commission from products or services I recommend. For more, see site policies.

Hi Marek,

I am looking to do the 3-day Ijen-Bromo tour solo in a month solo. Unfortunately all the tours I have come across so far only provide this tour for a minimum of 2 people…

Did you book this tour solo ? If you can you give me a link or the name of the tour company you used ?

Thanks so much!

Esmé

Hey Esme – yes I was solo and I booked it locally via Venezia Garden hostel in Yogjakarta. When you’re researching online you’ll probably find more higher-end tour companies that do tailored stuff for individual couples/groups. What you’ll probably want is a tour company that puts their customers into mixed groups, which may be easier to find in person in Java. To be honest I don’t remember the name of the tour company – it’s one of those situations where they give you a little hand written receipt and a guy in a minivan just comes to pick you up…